Prison food has been in the news. In a terrible incident, the brother of the Manchester bomber caused life-changing injuries to several prison officers due to his access to cooking facilities. It’s clear that good food can positively affect inmate behaviour. Yet recent events could mean that prisoners no longer have access to kitchens.

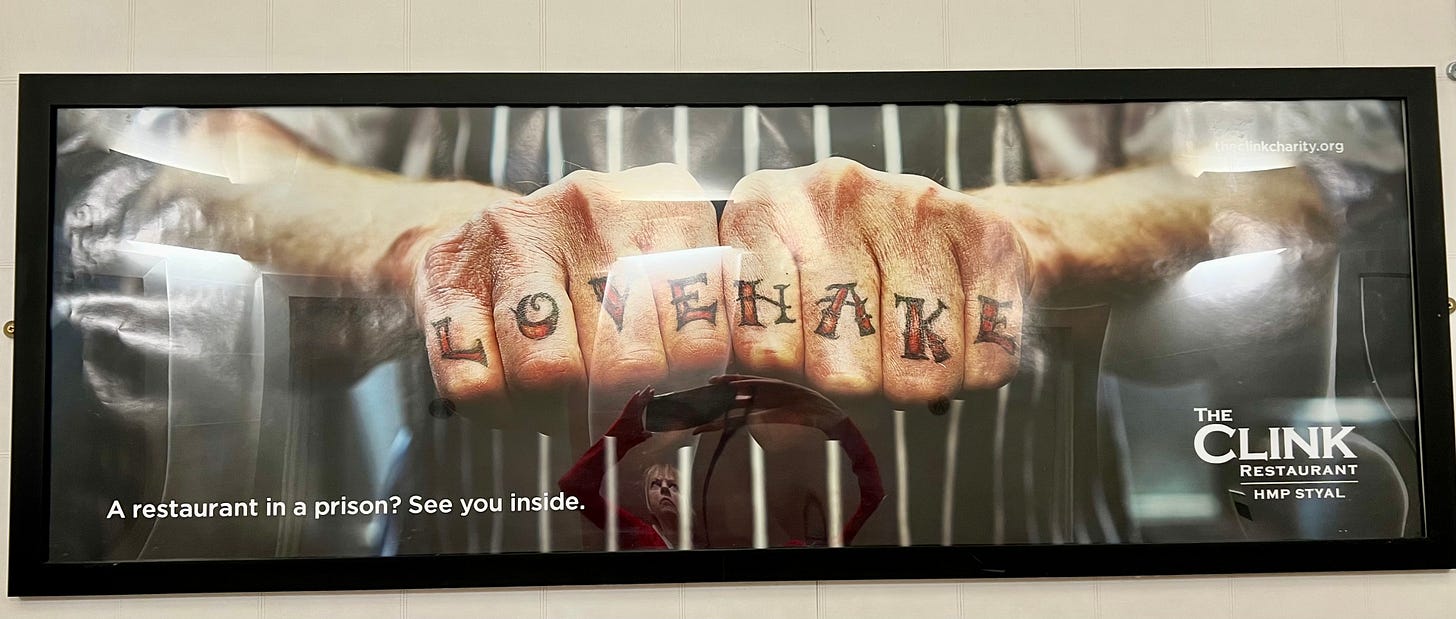

After my visit to The Clink prison restaurant in Brixton, I took the train up to Styal in Cheshire to visit another part of The Clink project, a restaurant housed in a former church. It was a bright day and streams of sunlight filled the tall beamed ceilings. This looked like a very posh restaurant.

Unlike Brixton, there are no security measures as you walk in. No taking of your passport, no body searches, no frisking, no scanners. I walked in directly from the outside.

Prisoners on the training scheme can walk from the open prison to work at the restaurant unaccompanied by prison staff.

I talked to Gail Gardner-Harding, the South African General Manager Trainer. ‘All our restaurant workers, we call them students, are Cat D prisoners who are rotling; ROTL (an acronym) meaning they are released on temporary licence.’

Female prisons, because there aren’t many female prisoners, cater for all categories, from the most serious Category A through to D. Male prisons tend to house one category only. In Styal, the few Cat A prisoners are on their own wing and segregated.

Styal used to be a children’s orphanage. As such, the buildings, where women are housed in dormitories and single cells, appear from the outside to be grand Edwardian houses.

One section of the prison is open, housing Category D offenders, who are considered low-risk and unlikely to abscond. The goal is to rehabilitate these prisoners, who are in for fraud and other non-violent offences.

The stats:

The Styal inmate population is around 400 prisoners. In the UK, there are around 4,000 female prisoners, compared to 85,000 male prisoners. Of these women, two thirds are jailed for non-violent offences. Most have children. When a woman is jailed, the ripple effect is far-reaching and a serious matter for families. Children are then put into care, which has a knock-on effect.

The Labour government freed thousands of prisoners when it came to power last year. Gail said there are still only 100 places left overall.

The training:

I asked Gail whether the students had any preference between cooking and baking. In professional kitchens, women tend to be pastry chefs.

‘The qualification we do is a combined one, so there is pastry element to it. The NVQ professional cookery level 3 encompasses the whole (range)… So we don't specialise in just pastry. They get a taste of everything, spending a couple of months on each section.’ The course is nine months in total. Civilian chefs work alongside the students.

How do you choose who gets to work here?

‘As soon as they’ve landed [the expression used for entering prison, like a fish], they get assessed: their work experience, and what they want to do with their time in prison, what training they’d like to undertake.’

So, from the get go, you are looking ahead to when they are released?

‘Yes. We don’t turn anybody down. We do risk assessments. Everyone gets a two-week trial,’ she said.

‘Once they become open category prisoners, if they choose a catering path, they can go work in the community on a daily basis and then come back every night, so they'll be released on temporary license, which is ROTLed to go and work out in the community or with us.’

Have you had any runaways?

‘Only a couple during my time.’ She added: ‘It’s not worth it, though, because they immediately lose all their privileges, such as days with their families. They get put back into the secure prison.’

Many of the prisoners are on remand, which means they are not on open prison status and therefore cannot work in the restaurant. They can do educational courses. They can also work in The Bistro, which is the staff canteen for the prison officers.

I ask about remand prisoners. There is a backlog in the courts, exacerbated by COVID. Saffron, a support worker, tells me: ‘Some of the girls who might be here waiting three years on bail, and then they've come to custody three years later, which, to me, is just pointless, like, manage that person in the community. They've already been on bail. Why are you now coming to prison? By the time they get to court, they’ll get time served, be released, but by then, they might have lost their flat, their children, things like that. These people can be managed in the community, especially low-risk offences.’

Here is a link to a great article in The Spectator by a woman who taught some of the prisoners (subscription needed).

Life inside

As for the inmates’ food, they get a rolling monthly menu for each meal and there are options: vegetarian or halal, for instance.

The budget for prisoners food is approximately £2.60p per meal. It’s hard to buy fresh nutritious food for that sum.

Prisoners don’t get access to sunshine as much as the rest of us, I wondered whether they get supplements such as Vitamin D. I noticed in my visit to Brixton prison that you could tell who were the prisoners as they were so pale.

Some of the houses they have access to kitchen so they can self-cater. Inmates also have a canteen where they can pay for food with their own money. It depends on the prison, but they earn between £4 and £5 a day.

On the outside, that's enough to buy a sandwich?

'Obviously everything else is provided for them,’ Gail said. ‘That money goes towards what you probably class as their luxuries, as in chocolates, crisps, things like that. They do all get provided with toiletries, but if you wanted a specific brand, you could buy that.’

Are prisoners allowed to wear makeup?

‘They have Avon ladies. They can order off Zoom.’

Can they wear their own clothes or is there a uniform?

‘You can wear your own clothes. You can have your own clothes from home sent in, which needs to be checked, etc. But the prison will provide them with track suits. So you have a choice. A lot of them, depending on where they're working, will have a uniform anyway, so the chefs will have chef whites.’

The food:

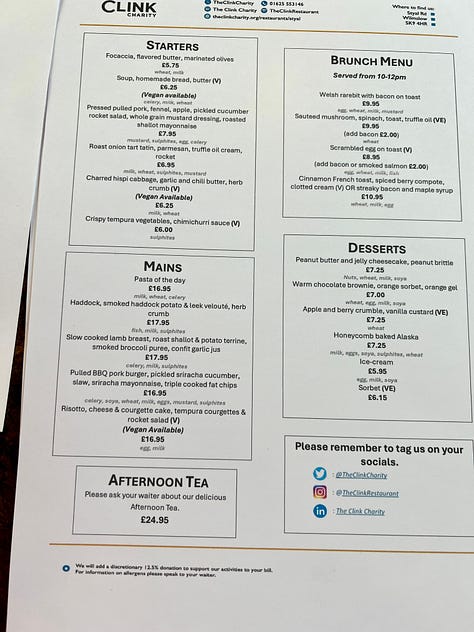

The food is, as in Brixton, excellent. For starters I had a charred hispi cabbage with a green herb crumb, lemony and just the right amount of salt.

For the main course I chose an unusual risotto pie, rather like a rice frittata, light and herby with rocket and tempura courgette chips.

Dessert was a honeycomb ice cream Alaska with a salted caramel insert.

Part of the training concerns dietary requirements. Gail said more customers are vegetarian and vegan than previously. ‘Gluten is a big one. Because we are a training restaurant, the chefs teach the students a lot about how to adapt different dishes, what they can and can't use. Our sauces are generally all gluten-free, only because it is a lot easier to produce that. But it doesn't mean that we don't show the students the way of making your bechamels. We don't veer from making a bechamel. But we accommodate where we can. ‘

The students:

Hannah on front of house, before being incarcerated, had worked for a housing association.

Doing admin? I asked.

‘Working with anti-social behaviour.’

What are you going to do when you leave?

‘I might do my masters.’

What was your degree?

‘Criminology.’

I wondered whether she was doing some kind of deep-dive research by actually being in prison.

In the kitchen I met three students. There was a fourth but I wasn’t allowed to take her picture because of ‘victim support’. I assumed that meant that her victim would be upset if she saw pictures of her.

One, a hairdresser before prison, had a Persian background. I remarked that hairdressing was similar to cooking in that it requires manual dexterity – it’s all about working with your hands.

Another was a 26-year-old girl who had never cooked before: ‘This has introduced me to lots of new foods. I never liked olives before but now I love them.’

What do you like to cook?

‘I love making soup and focaccia. It’s the smell of home.’

Another woman had worked in food before, cooking for a homeless shelter.

‘I like to make Sunday roasts. I’d like to have my own restaurant. When my dad dies, I’ll inherit some money, so I can do it then.’

Having their own restaurant was a common ambition amongst students.

The guests:

‘Most of our guests tend to be retired. They are the only ones who can come during the day. When we are open Friday evening and Sunday, the demographic is very different,’ Gail explained.

I chatted to a long table of grey-haired women who were a local flower arranging group. They meet once a month to watch demonstrations on how to make bouquets.

A large group of criminal justice students came in, filling up a long table. They were here from the States, Rutgers university in New Jersey, with their professor. They are doing a tour of prison programmes. They’d already visited the Brixton restaurant.

‘Now we are staying three days in Leeds, then on to Belfast to do an ‘IRA tour’. We don’t have programmes like this in the States. We have 50% recidivism in the US if you’ve done three years in jail. After a programme like Brixton, recidivism is 11%.’

Transition to the outside:

I spoke to Saffron who helps prisoners get ready for release.

‘We work with the girls up to their release. So we'll do an assessment about what they need, support around accommodation, get them employment ready whilst they're here, update CVs, help out disclosures around their offenses, and then get them primed and ready. We will do interviews here. Had a lady recently who's just interviewed for San Carlo [a restaurant chain with a Manchester branch].’

She added: ‘There might be local restaurants where the girls might go out to work in the daytime after they finish here at The Clink. We support for 12 months after release, doing anything, whether it's mental health, employment, accommodation…’

‘It is all about giving people a second chance. We have some ladies who are perfectly able to read and write, and then we have other students who either have dyslexia or haven’t finished school, where they don’t have the ability to to do all the paperwork. We'll help them through that as well.’

Employers are perhaps keener to have them in the kitchen, rather than interacting with the public. ‘We find that often it's harder to get girls positions such as front of house or barista, although we still work with Starbucks, Costa and Green King. We've had a lady recently. She's doing a split role: two days front of house, and then she does pot wash in the kitchen. She’s never worked before,’ Saffron said.

‘She had quite a lot going on, her situation, relationships, and she did struggle with addiction but now she's come here. She's been amazing. She's got her own flat again. Got her life back on track.’

So, in a way, a prison sentence has transformed her life for the better. Or is that saying too much?

Saffron: ‘I think some ladies come through prison, and it really is a turning point in their life where they get help with substance misuse issues. They get somewhere to live. They might have years of being entrenched rough sleepers or homeless or in abusive relationships, and they come here and they set themselves back up.

‘Whereas some of the other ladies who come in for the lower risk offenses, it can turn their life upside down, because they then lose their accommodation, they lose their job, and things can go really wrong. We do pick up a lot of messy situations, sometimes saving tenancies, helping people set back up. So it's different. It's case by case.

‘The early release scheme that's coming in, that's positive change. Some of the women, with really low risk offences, can be managed in the community. It's not just the shoplifting they've done, or committing an offence because they want to do it. It's because of their circumstances where they've got no money, or homeless, or trying to feed the children, that's how a lot of the women end up in the criminal justice system. Some of the women who do come through have been in care themselves.

‘They're reintegrating back into society. They've got a little bit of a purpose. Some people never worked before, so coming here and training, we've had girls come through and they absolutely love cooking, and never done anything like that. Even just having them skills, even if someone's not employment ready, they're going home and cooking for their children. They learn about nutrition as well and that impacts that your life in general.’

Saffron estimates that around 50% of the women are in jail because of drug or alcohol addiction. ‘I think people use substances, alcohol or drugs to deal with trauma that dogs them in their life. ‘

As we know, mental health services in the NHS are overrun. It’s much harder to access support in the community. Gail pointed out: ‘When they are in custody, I think they are able to access support a little bit easier.’

His Majesty’s Prison Inspector released a report in March this year which revealed Styal has the highest positive drug test results in the women’s estate and the second highest rate of self-harm. It also suffers from a surfeit of suicides. This project is extremely important to prevent reoffending.

How can you support The Clink?

By visiting the restaurant:

The Clink at Styal It’s open for lunch, afternoon tea, Friday night dinner and Sunday lunch.

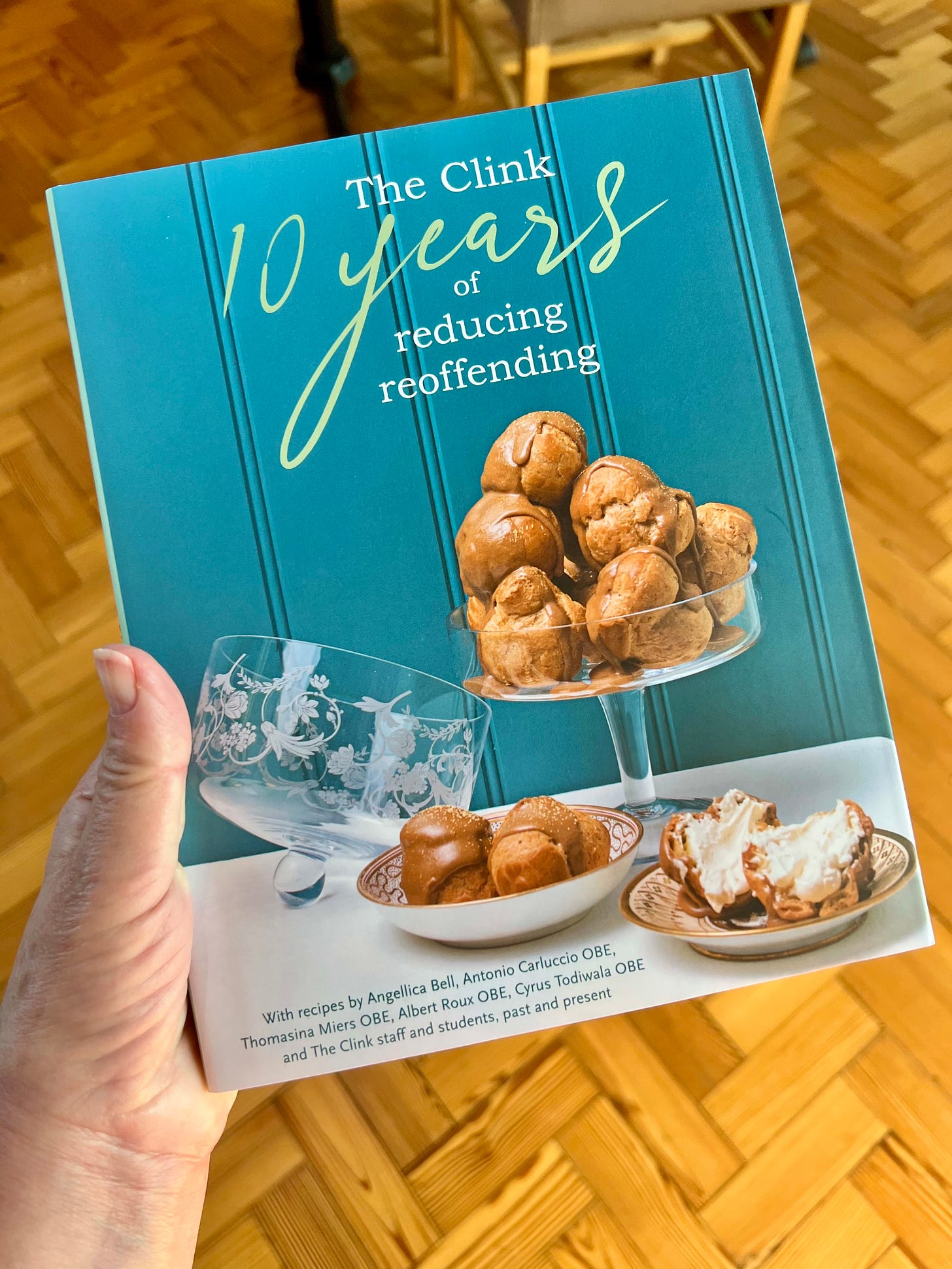

Buying their books:

The Clink Quick & Easy Cookbook

The Clink Fruit and Vegetable Cookbook

Great piece Kerstin... and wonderful images too! xx